Maximising the benefits of Professional Learning Networks: finding ways to achieve research-informed practice at scale

Professional Learning Networks (PLNs) are increasingly being turned to by school and school system leaders as a means to drive school improvement. In many instances (e.g. Research Learning Networks) PLNs are focused on driving research-informed change at scale. This blog presents findings from our recent work in this area, and examines how to maximize the impact of PLNs so that all teachers and students benefit. We begin by exploring the vital role of distributed leadership.

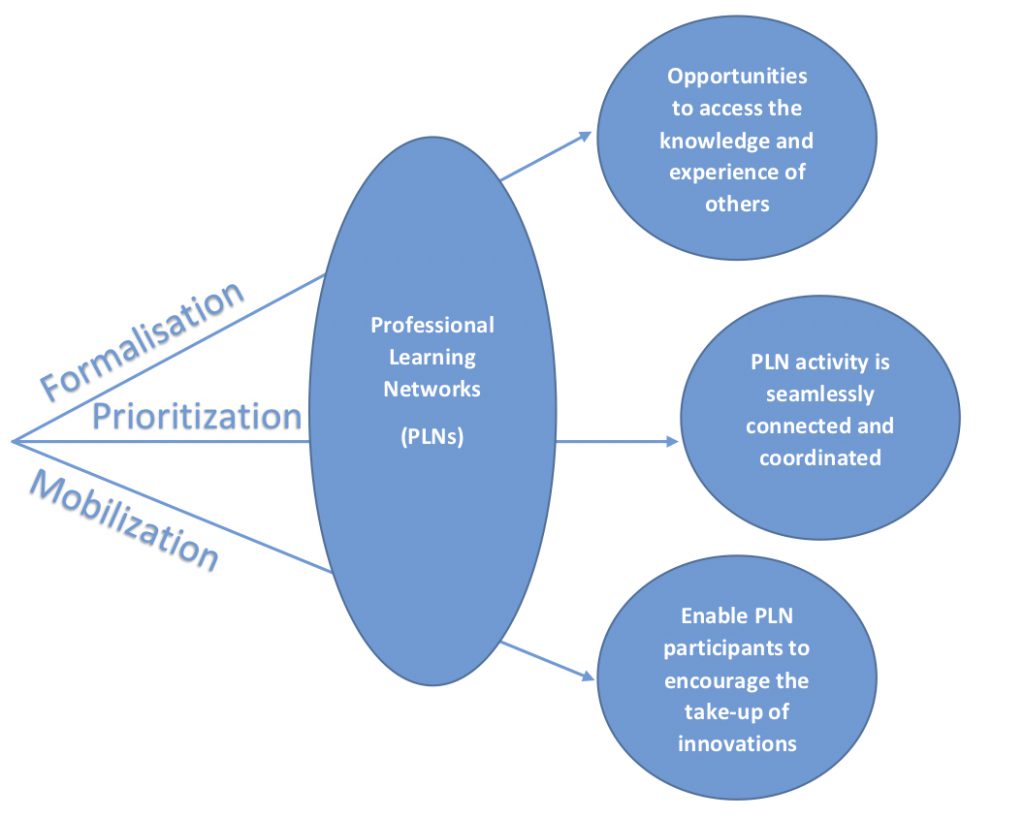

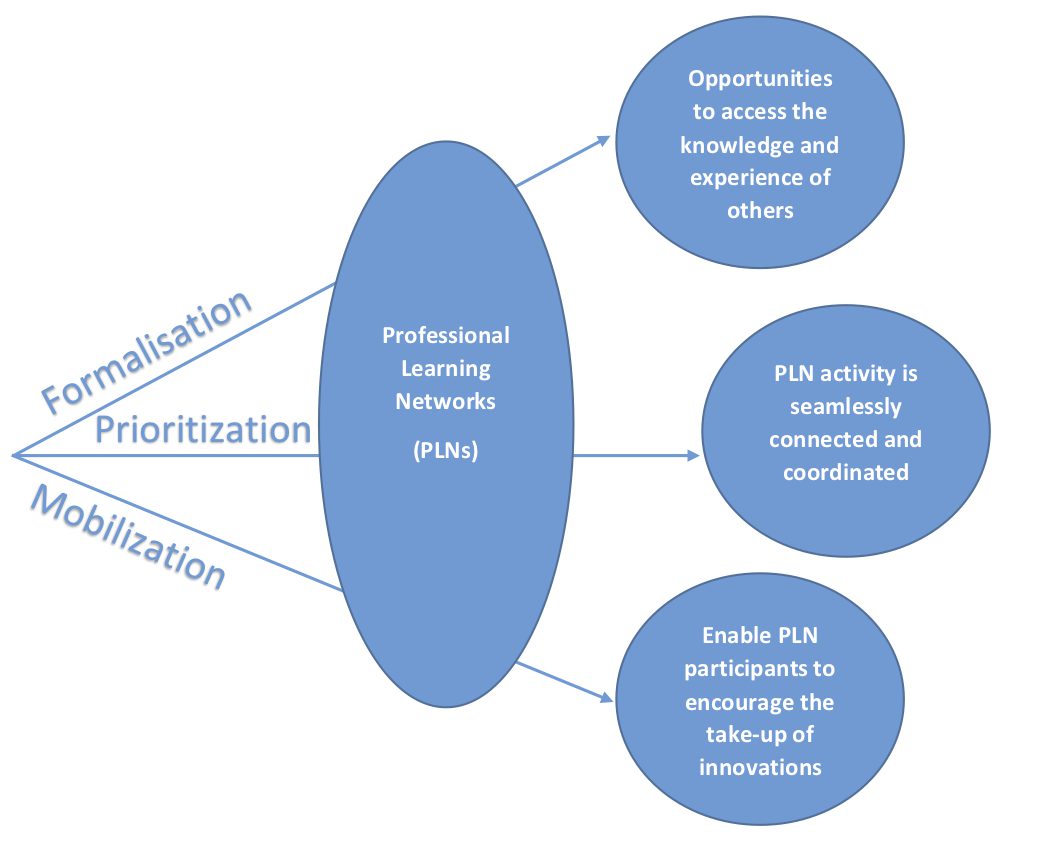

Distributed leadership (DL) is acknowledged as an effective means to improve teaching and learning in schools. Our work has shown that models of DL can serve to effectively connect networks and schools. In particular this is effective when approaches to DL:

- provide PLN participants with the opportunity to access the knowledge and experience of others. In turn this enables PLN participants to harness the expertise they need to engage effectively in PLN activity;

- ensure PLN activity is seamlessly connected and coordinated with the more traditional hierarchical decision-making structures of the school. As a result, participants are granted the autonomy and freedom to engage in or lead innovation, as well as mobilise innovations, so that all staff benefit;

- enable PLN participants to encourage the take-up of innovations. For instance, DL approaches could see PLN participants acting as champions of new research-informed teaching and learning practices, so encouraging their use. Or DL could also materialise by PLN participants taking school staff through a process of discussion and the collaborative trial and refinement of research-informed innovation.

At the same time, a distributed leadership approach needs the support of school leaders if it is to be effective. In particular, school leaders need to ensure that PLN participants are empowered as leaders; that they are afforded opportunities to interact with others; and that they are able (i.e. have the skills, experience and knowledge) to lead. Regarding this last point, PLN participants have a particular need in terms of understanding how to lead change effectively, so that they can mobilize innovations; whether acting as an innovation ‘champion’ or through leading learning conversations. At the same time, embracing distributed leadership also requires the networked school leader to recognize that their role must necessarily change to accommodate this expansion of leadership responsibility. In particular, that the networked school leader should be regarded, and should also see themselves, as a facilitator, as an expert source of advice and as an able coach. And they must use these capacities to grow the next generation of instructional leaders through a mixture of counsel and organizational re-structuring. In addition, networked school leaders need to also be without ego: they need to have the confidence to relinquish power – and to not try and grasp it back at the slightest sign of failure – while supporting others to lead themselves. These new requirements are not without challenge and it may be that these requirements should be included and supported as part of leadership training moving forward.

What else do we now know?

At the same time, school leaders may find themselves not yet ready to embrace approaches to distributed leadership. If this is the case the following lessons learned from this work can also help school leaders to maximize the benefits for their school of engaging in PLNs:

Formalisation: It is vital that networked activity is formally linked to the policies and process of the school. Doing so signals the importance of the work. Also that engaging in networks is not ‘just another initiative’, but something that is key to a school’s culture and way of working. Approaches to formalizing PLNs encompass the inclusion of network-related activity in school improvement plans and teachers’ performance management targets. Also by ensuring that PLN engagement is on the radar of the school’s governing body. It can also occur through agreements with any staff bodies responsible for delivering change in schools. At the same time, such signals need to be meaningful. There is no point adding priorities to a school improvement plan if there are already so many that the notion of something being a ‘priority’ no longer has currency.

Prioritization: Ask any teacher around the world how they could best be supported to engage with a new initiative and, invariably, time will feature in their response. Teachers are overburdened and if we want them to do more of something, we need to ensure they can do less of something else. Often school leaders have the freedom to change structures within their school to free up time. For example, by ‘shaving’ time from lessons to create a free half day once a week; by reallocating meeting or preparation, planning and assessment time; or through smart approaches to timetabling. Affording time to teachers will go a long way to helping them engage in PLNs effectively, but time also needs to be allocated to help teachers engage with their colleagues to ensure the mobilization of activities can occur. This also means that processes within the school should be used to facilitate PLN-related collaboration. For instance timetables should reflect that the need for collaboration between particular groups of teachers.

Mobilization is complex and teachers and school leaders still have much to learn in this area. Our work in this area suggests that the most impactful forms of mobilisation involve school staff: 1) actually engaging with innovations; 2) collaboratively testing out how new practices can be used to improve teaching and learning, and; 3) continuing to use and refine new practices in an ongoing way. This is because supporting staff to actively engage and experiment with new practices helps them to develop as experts. In turn this means that the use of PLN-related innovations will be both refined and sustained over time, allowing students to benefit from their ongoing improvement. In addition, who is doing the mobilizing matters. Ideally PLN participants should be situated at the centre of their school networks meaning they have the power, the access and the ability to influence whether and how innovations are adopted by others.

About the authors:

Professor Chris Brown is the Director of Research in the School of Education at Durham University in England. He aims to improve both teaching practices and student outcomes by emphasizing the importance of Professional Learning Networks (PLNs). He can be reached at chris.brown@durham.ac.uk.

Jane Flood is the Head of Learning at Oaks CE Learning Federation at Netley Marsh School in Southampton, England.

Stephen MacGregor is a doctoral student at the Faculty of Education, Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada. His research focuses on how education stakeholders can build their capacity in knowledge mobilization to impact research. Stephen draws from traditions of mixed methods and social network theory in order to identify and describe information in multistakeholder networks. He can be reached at Stephen.macgregor@queensu.ca.

Published by