Use of Evidence to Inform School and District Budget Decisions

Every year schools and districts spend considerable amounts of time and effort allocating their annual budgets (AASA, n.d., Peterson, 1991). The process invariably involves many spreadsheets, procedures and meetings. But to what extent is research or other evidence used to inform budget decisions? As part of our work together in an IES-funded research-practice partnership, we addressed this question by reviewing 55 requests for discretionary funds submitted by school principals and district administrators in a large, southern school district. We conducted a document analysis (Bowen, 2009; Gitomer & Crouse, 2019) of these budget request proposals, specifically looking for evidence to support the effectiveness of each proposed investment at improving educational outcomes.

Setting the stage

A little background on the district’s budget process: each school and district office division is allocated a budget amount each year, but principals, district office division chiefs, and program directors (“cost center heads”) are often able to apply for extra funds from the district’s discretionary budget. Cost center heads must complete an online budget request proposal which district office senior leaders review when deciding whether to approve each request. In addition to descriptive information about how the requested funds will be used, applicants are asked to provide an evidence base; specify the target student population, its demographics and needs; report baseline and target student outcomes; and outline implementation plans. It is worth noting that 52 of the 55 requests were partially or exclusively for personnel, mostly assistant principals, mental health counselors, interventionists, and coaches.

Evidence used to support requests

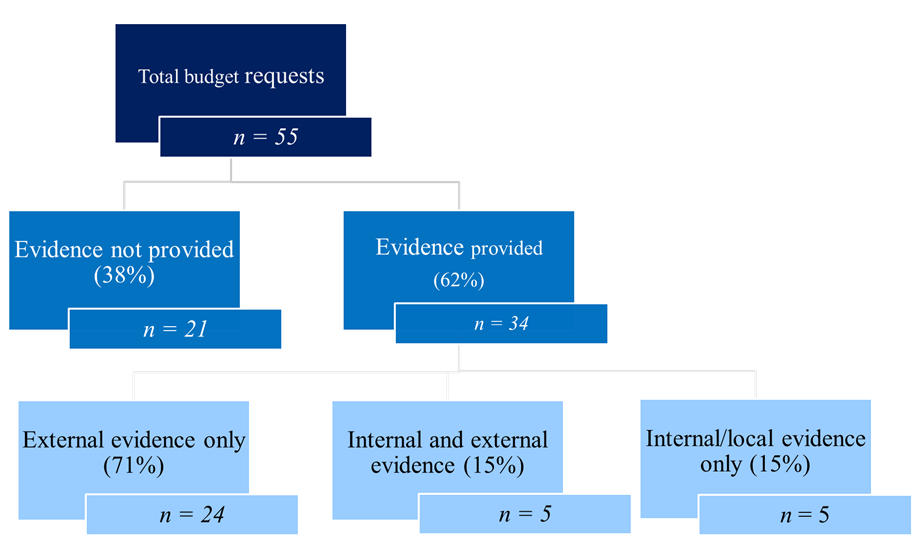

We found that 38% of the requests provided no supporting evidence while the other 62% did. Cost center heads who did provide evidence listed between 1 and 24 pieces of evidence to support their proposed strategy. We observed that, even when several cost center heads requested funds for the same strategy, some cited supporting evidence while others did not.

We categorized the evidence in several ways. First, we bucketed the items as external evidence or internal evidence following Hollands and Escueta’s (2019) definitions of internal and external research. We found 33 pieces of internal evidence, often in the form of school or district data showing changes in student outcomes. We identified 105 pieces of external evidence. We reviewed each piece of external evidence and categorized it by type of publication and study design using categories similar to those used by Davidson, Farrell and Penuel (2018) and by Farley-Ripple and Jones (2015).

Encouragingly for the researchers among us, the most common type of external evidence cited was a journal article. It’s reassuring to know that decision-makers do actually notice our work. However, one third of the evidence cited used no recognizable research method and only 6% was based on experiments.

Theory of Change Considered

Lastly, we made a judgement about whether each piece of evidence supported the theory of change implicit in the budget request. We found that less than one third of the internal evidence items and just over half of the external resources cited supported or partially supported the budget request’s implicit theory of change. One piece of evidence actually showed that the proposed strategy resulted in worse student outcomes! This does raise the question of whether the evidence cited was read and influenced the decisions, or was simply tacked on to satisfy the evidence requirement.

It appears then that, even if school and district administrators are asked to provide an evidence base when submitting budget requests, they only refer to evidence supporting the effectiveness of the proposed strategy for around 60% of their requests, regardless of whether or not such evidence is available. Less than 40% of the external resources cited appeared to support the budget request’s theory of change.

Hypothesized explanations

We hypothesize three explanations for why budget requests were not consistently supported by evidence. First, the evidence base may be lacking for the types of strategies proposed. It is certainly the case that repositories of evidence such as the What Works Clearinghouse and Evidence for ESSA do not house studies demonstrating whether hiring additional assistant principals or counselors leads to better student outcomes. Given that the vast majority of school district funds are spent on personnel – 80% according to McFarland et al., 2017 – there does appear to be a gaping hole in the evidence base. Second, cost center heads may not have the necessary training and expertise to formulate evidence-based theories of change and to evaluate the evidence that does exist. Third, the cost center heads may have perceived the evidence requirement as optional because requests were still considered even when no evidence was provided.

Suggestions to improve use of evidence to inform budget decisions

To address these possible causes, we came up with a few suggestions for improving the use of evidence to inform budget decisions:

- More research is needed on the effectiveness of education personnel and the specific practices in which they engage. This could contribute to a database of items in which schools/districts most commonly invest, associated evidence of effectiveness, summary ratings, and implementation details to help cost center heads and district office approvers make better decisions about where to invest funds.

- District office cabinet members who approve budget requests should clarify the type of evidence, whether local data or external research, they expect to see justifying budget allocations. In addition, they should require that budget requests include an explicit theory of change to demonstrate how the investment is expected to lead to better student outcomes. They should question any request that is not supported by adequate evidence or where the evidence is not aligned with the theory of change.

- Districts should offer training to administrators in:

- Developing logic models/theories of change to support their budget requests with appropriate student or staff outcomes, tangible metrics, and reasonable targets for improvement.

- Identifying evidence-based strategies to address student or staff needs, either using local data or external research.

- Determining what counts as rigorous evidence and assessing the strength of an evidence base.

Longer term, it would be valuable to investigate whether budget requests to fund strategies supported by stronger evidence are ultimately more likely to meet their target outcomes than those supported by weak or no evidence. We’ve started to do this by calculating “academic return on investment” on a few of the investment items funded by these budget requests. But that’s for another blog someday.

References:

AASA. (n.d.). School budgets 101. American Association of School Administrators. Retrieved from https://www.aasa.org/uploadedFiles/Policy_and_Advocacy/files/SchoolBudgetBriefFINAL.pdf

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27-40.

Davidson, K. L., Penuel, W. R., & Farrell, C. C. (2018). What counts as research evidence? How educational leaders’ reports of the research they use compare to ESSA guidelines. Abstract from 2018 Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness Conference, Washington DC.

Farley-Ripple, E., & Jones, A. R. (2015). Educational contracting and the translation of research into practice: The case of data coach vendors in Delaware. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 10(2), 1-18.

Gitomer, D. H., & Crouse, K. (2019). Studying the use of research evidence: A review of methods. A William T. Grant Foundation Monograph. Retrieved from http://wtgrantfoundation.org/library/uploads/2019/02/A-Review-of-Methods-FINAL003.pdf

Hollands, F.M., & Escueta, M. (2019). How research informs educational technology decision-making in higher education: the role of external research versus internal research. Educational Technology Research & Development. DOI: 10.1007/s11423-019-09678-z

McFarland, J., Hussar, B., de Brey, C., Snyder, T., Wang, X., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Gebrekristos, S., Zhang, J., Rathbun, A., Barmer, A., Bullock Mann, F., & Hinz, S. (2017). The condition of education 2017 (NCES 2017-144). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2017144.

Peterson, D. (1991). School-based budgeting. ERIC Digest, 64, 1-7. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED336865.pdf

About the authors:

Fiona Hollands is a Senior Researcher at Teachers College, Columbia University. Her research focuses on optimizing the use of resources in education by assessing costs as well as effectiveness, benefits or utility of educational programs, practices and strategies. Fiona can be reached at fmh7@tc.columbia.edu.

Dena Dossett is Chief of Accountability, Research, & Systems Improvement Division at Jefferson County Public Schools, KY. She manages the district offices of planning and systems improvement, research and program evaluation, testing, and resource development. The division’s research efforts are focused on evaluating major district initiatives and providing data analysis support to schools and central office departments. Dena can be reached at dena.dossett@jefferson.kyschools.us.

Published by