Where is the disconnect?

Knowing how the use of research varies along multiple dimensions serves only to inform about the nature and scope of knowledge utilization. To identify strategies that can make research more meaningful to education practice, it is critical that we also ask: what factors explain the variation in schools’ use of research? To guide our exploration, we examine the cultural differences between the two communities of research and practice.

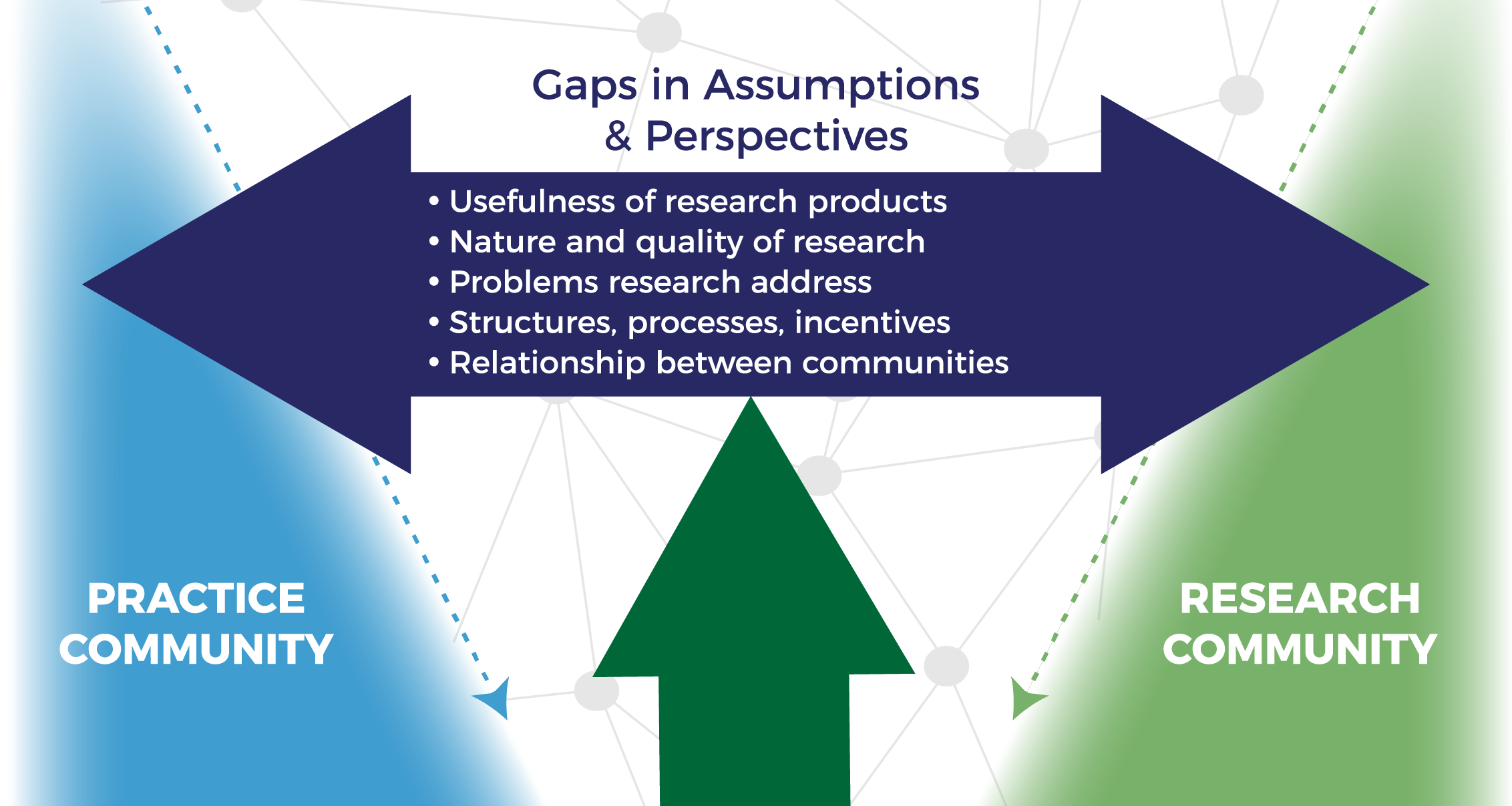

The Center’s work seeks to understand not only the extent to which research use is impacted by the cultural differences between the research and practice communities but also to identify the practices and conditions under which these gaps can be bridged to produce meaningful interactions.

- Usefulness of Research Products: The type and characteristics of research publications and resources influence their use in schools. From the research community perspective, usefulness can be understood as the range of products produced, their intended audience, and how they are anticipated to be used. From the practitioner perspective, usefulness relates to frequently accessed resources and the preferences underlying those choices. The extent to which the products valued and produced by researchers intersect with those preferred by practitioners indicates the usefulness dimension of the gap.

- Nature and Quality of Research: The research and practice communities value different qualities of research regarding study design and conclusiveness of findings. For example, the What Works Clearinghouse places great weight on studies using a randomized controlled trial design, leading to unbiased findings. In contrast, school-based decision-makers often prefer evidence from organizations similar to their own, regardless of study design. These preferences raise questions about how practitioners value research methods. The extent to which researcher standards and practitioner preferences are similar or different is an indication of the nature/quality dimension of the gap.

- Problems Addressed by Research: Each community may view the role of research differently in solving problems of practice. The research community perspective seeks to answer what should be researched and to what degree research is able to address current problems of practice. The practitioner perspective views the characteristics of problems of practice as important in influencing the role of research in solving those problems. The extent to which the evidence produced by the research community is timely and relevant to the problems confronting real schools is an indicator of this dimension of the gap.

- Structure, Process, and Incentives: This dimension of the gap focuses on the context in which researchers and practitioners operate, what influences researchers to produce certain kinds of research, and what influences practitioners to use research or other evidence. A range of conditions influence use, including organizational structure and culture. As contextual factors related to structures, processes, and incentives influence research use, it is important to understand when and to what degree these factors increase or reduce the gap between research and practice communities.

- Relationships between Communities: Research use may also be considered a function of the relationship between the research and practice communities, which can take three forms: producer-pushed (e.g. dissemination), user-pulled (e.g. active search by users), and exchange (e.g. interaction between users and producers during key processes). The nature and extent of interaction between individual researchers, or research organizations, and practitioners is an indicator of the relationship dimension of the gap.

- Purpose: Each community may view research as having a different purpose. How practitioners use evidence in schools may differ from how researchers intended their work to be used. Research is used in four primary ways, described below.

- Instrumental: Using evidence to address a specific problem.

- Conceptual: Creating gradual shifts in awareness of basic perspectives as new knowledge is incorporated into current thinking.

- Strategic: Manipulating evidence to attain specific power or profit goals. For example, studies provide examples of how district central office administrators used evidence to confirm or justify opinions they had already formulated.

- Symbolic: Believing that evidence-based decision-making is important, but engagement with or application of the evidence in meaningful ways is absent. For example, referring to research findings in vague or general terms like, “the research says,” is common in evidence-based decision-making.

Instrumental USE and Research4Schools

Strategic and symbolic uses of research are not likely to improve evidence-based decision-making in practice. Additionally, conceptual use of research reflects a change in educators’ working knowledge; however, it is also not likely to improve decision-making since it is more associated with changes within individuals rather than systems. Therefore, our Center emphasizes instrumental use in our depth of use measures. By focusing on instrumental uses of research, we are better able to understand the specific role research evidence plays in decision-making, the types of decisions or problems research is most likely to inform, and the types of research used by decision-makers in those processes.